You don’t have to travel far within either fantasy or science fiction before you trip over an empire. If anything, in fact, they’re even more prevalent in SF than in fantasy, from the empire of the Klingons and the one that strikes back to the enemies of the Foundation and of the Atreides. Most are evil empires (largely because we prefer to support the little people) but not all.

But what actually is an empire? And, just as importantly, what isn’t? It’s one of those words we all assume we understand, but actually the concept of an empire is an accident of history that’s not easy to pin down.

What’s an Emperor?

OK, surely the simplest definition is that an empire is ruled by an emperor. Or an empress, of course, though historically there have been very few regnant empresses. 1 As we’ll see, this is by no means always true — but it still begs the question of what an emperor is.

Surprising as it might seem, the title emperor actually started life as a military rank. The Roman rank of imperator (emperor is just the slightly mangled English rendering) was roughly equivalent to the modern field marshal, and most often referred to the commander-in-chief of the army under the Republic.

This was just one of the many positions of power accumulated by Augustus, the first Roman emperor, and passed on as a package to his successors. The full package gave Augustus control over virtually every aspect of Roman life — but it probably reflects the Roman psyche that it was the military rank that came to define his rule.

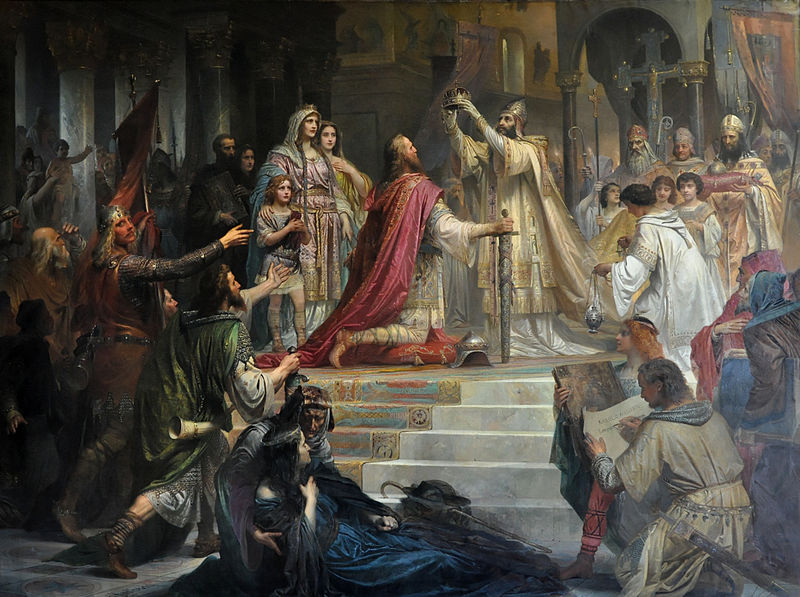

The last western Roman emperor, Romulus Augustus, abdicated in the year 476, although the line of emperors continued for nearly another thousand years in Constantinople. Much of later European history, though, consisted of attempts to revive the lost empire, and a whole series of rulers, starting with Charlemagne, had themselves crowned emperor in an attempt to identify themselves with the Caesars. 2

From Charlemagne down through the Holy Roman Emperors (a title that didn’t appear till the 12th century) to Napoleon and the Austrian and German emperors (and others from Spain to Bulgaria) all these were consciously trying to be the heirs of Augustus. In the east, the Russian emperors (styled tsar or czar) were similarly emulating the eastern Roman (or Byzantine) emperors. But what about emperors elsewhere in the world?

The traditional rulers of China (till the early 20th century) and Japan (ongoing) are conventionally referred to as emperors. However, the actual titles (Huangdi in Chinese and Mikado in Japanese) have names meaning Son of Heaven and Ruler from Heaven, respectively. 3 Neither has a trace of the military origins of emperor. And this is much the same for the “emperors” throughout Asia, Africa and the New World, from the Ottoman sultan to the Aztec huey tlatoani.

Empires Without Emperors

In fact, even if we take the attitude that all these titles are “close enough” to meaning emperor, by no means all empires have had a ruler with a special title. Many (the Persian and Macedonian empires, for instance) had rulers who simply used the same title as lesser kings. I have such an empire in my works. The ruler’s subjects call her the Queen, whereas her enemies call her the Demon Queen.

The British Empire never had an emperor, either. Victoria’s imperial proclamation in 1877 was specifically as Empress of India (in succession to the recently deposed Mughals), not as British Empress. Outside India, she was still a queen.

Empires don’t even need to have a monarch at all, whatever they’re called. The Roman Republic had effectively ruled an empire for a couple of centuries before Augustus. This was officially governed, like the city itself, by the Senate and Roman People, although this became increasingly nominal as a series of generals (Sulla, Pompey, Caesar, Augustus) seized effective power.

Another notable example of a republican empire was the Athenian Empire of the 5th century BC. This started life as the Delian League, an alliance of equals against the Persians, with Athens simply as the most powerful member. Gradually, however, Athens tightened its hold on its allies, to the point where they were punished with extreme prejudice for wanting to leave.

And that process continued. During the Cold War, arguably both the USA and the USSR had empires — neither ruled by an emperor or empress.

What Is an Empire — and What Isn’t?

Perhaps the most sensible approach would be simply to ditch the whole idea of emperors to define an empire. The previous section shows that we recognise an empire when we see it. So what defines it? And why are other political solutions that look similar not empires?

The simplest definition is that it’s an empire when one state, whether a kingdom or a republic, has gathered others under its control, whether by conquest, alliance or economic pressure. It’s a reasonable working definition — but not necessarily adequate.

After all, many modern nations originated that way, certainly in Europe and much of Asia, but we don’t regard them as empires. The Kingdom of England, for instance, later subsumed into the United Kingdom, was originally many kingdoms — 1200-1300 years ago, for instance, there were seven, though there had earlier been more.

They generally recognised a bretwalda (essentially a high king) who had seniority over the other kings without being officially their overlord, and eventually this passed to the kings of Wessex, including Alfred the Great. Gradually, through a process of conquest, marriage and liberation from the Danes, the Wessex kings evolved into kings of the English. 4 While that might have briefly seemed like an empire, this perception didn’t last.

Some nations, on the other hand, form as federal entities — such as the USA. While this model has some similarities to an empire, to the extent that it’s made up of a number of political entities ruled collectively, the difference is that no particular part of the whole has control of the rest. 5

So let’s adapt the working definition I gave above. Perhaps it would be more true to say that an empire is a collection of distinct ethnic and cultural areas that is ruled by one specific political/cultural entity among them, leaving the rest feeling distinct and disenfranchised. It can consist of contiguous or non-contiguous provinces — or it can consist of different planets, of course.

So that’s an empire. It doesn’t make much difference, of course, if all you want to do is boo the Evil Emperor — but hopefully it might help if you’re trying to make sense of the political state of the world you’re creating.

1 Wu Zetian, Empress of China from 660 to 705, is a notable exception.

2 Some used variations of imperator, some of the name Caesar that became a synonym of emperor. These included the German Kaiser (actually, closer than our pronunciation to the original) and the Russian Tsar or Czar.

3 Approximately. Other similar phrases have been suggested.

4 This was the normal form until several centuries later — King of the English, King of the Franks, King of the Germans etc. The Kings (and Queens) of Scots maintained this form until the union of the crowns in the 17th century, while the Belgian monarch is still styled King of the Belgians.

5 That’s the theory, at least.

Image: The Coronation of Charlemagne by Maximilianeum München, 1903 (public domain)