Cautiously, Icerag the snowman opened one coal-eye and peered through the steadily falling snow. It was nearly dark, apart from the pools of streetlight and the glow from the houses of the Warms.

How had they made him this time? Warms could be cruel, and snowmen were at the mercy of their whims. One winter, they’d given him a courgette, instead of a carrot, as his nose, and everyone had laughed at him.

It must be nearly time for the First-Snow Feast, marking the start of the brief snowman year, a holiday to celebrate waking again for another winter. They always gathered at Crystal’s, so, with a glance to check he was unobserved, Icerag moved off. The journey was tiring, but not long. Crystal was only a few gardens over.

She looked radiant as always, at the centre of their group. The Warms who made her, year after year, paid a lot of attention to detail, and an icy shiver of desire passed through Icerag at the sight of her perfectly spaced eyes, the sweet little carrot of a nose and the delicious paunch of her belly. She was perfect, yet again.

Icerag experienced that strange melting feeling Crystal always gave him. To distract himself, he asked, “Everyone here?”

The mood immediately grew sombre. “No Snowflake again,” said Crystal.

No-one commented, but Icerag knew they were all thinking the same. Snowflake had new Warms, who hadn’t made him last year. It was every snowman’s dread.

“Never mind,” said Crystal determinedly. “The feast’s ready. We have a plump, succulent one this year. I don’t think it’s been missed yet.”

All the snowmen looked down at where a tiny Warm’s head poked out of the snow, its body buried deep enough to restrict movement. Its absurd eyes were darting all over the place, instead of staying still, but the snow packed into its mouth was stopping it from making any of their strange sounds.

“Perfect,” said Icerag. “Let’s eat.”

And half a dozen snowmen gathered around to begin devouring the little Warm. It was going to be a splendid feast.

Gerda and the Darkness Published in Death +70

My story Gerda and the Darkness was recently published in Death +70, the rather curiously titled anthology from the equally curiously titled imprint Harvey Duckman Presents. This is a collection of eighteen stories by a variety of authors, whose theme is described as “Tantalising Tales from Beyond the Apocalypse”.

The publisher describes it as “a disturbingly dark collection of post-apocalyptic and dystopian fiction, rich in zombies and plague, wasteland raiders and alien invaders, lost tech and ancient lore, nuclear Armageddon, the end of the world and beyond…”

Needless to say, I’m delighted to be in the anthology, especially as this is a story I’ve been trying to get published for some time. I wrote it ten years ago and was delighted and proud of it — but it was only after racking up nineteen rejections that Harvey Duckman finally accepted it.

Realistically, I have a good idea why markets may not have been falling over themselves to publish this story. Rather than being written in the immersive style popular today (and my more common approach to fiction), Gerda and the Darkness is more like a folk tale with a more traditional storytelling approach.

I’m realistic enough to understand this wasn’t my most saleable story —though more so than my still-unsold second person, future-tense piece (another one I still believe in). So It’s wonderful that Harvey Duckman seem to have seen in it what I always saw.

Nevertheless, it’s a little surprising that they saw it as fitting into this particular anthology. Although there is a hint of the dystopian, it’s definitely an outlier in the collection.

I don’t remember clearly what motivated me to write it, but one inspiration was probably the opening lines of Paul Simon’s song The Sound of Silence1: “Hello darkness, my old friend, I’ve come to talk with you again.” Allegedly (although I’ve no idea if this is true) it was a regular saying of a blind friend of Simon’s musical partner Art Garfunkel.

The story concerns Gerda, a young woman who lives in a traditional-style Scandinavian village on the hills above a fjord. No specific location is ever given, and I tend to think of it as a parallel version, rather than a real-world Scandinavia.

As a child who’s a bit of a loner, Gerda meets and befriends an entity called Darkness. Far from being scary or menacing, the Darkness becomes a good friend, telling Gerda endless stories, including some about the ultimate dark beyond any stars, which she loves.

When Gerda is a young woman, the community is threatened by raiders — but raiders like none they’ve heard of before. These come from a highly industrialised and urbanised society, with hints that it’s an expansionist dictatorship, who intend to exploit the land for its mineral wealth. And the people are simply in the way.

Without giving away any spoilers, it’s Gerda and the Darkness who save the day, and Gerda is rewarded with a somewhat twisted (but genuine) heart’s desire.

Gerda and the Darkness, along with the other seventeen stories, is available from Amazon as a Kindle, a paperback or a hardback. You can find it on Amazon.co.uk or Amazon.com — or just tweak the URL to fit your country’s version of Amazon.

I hope you enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed writing it

1 The title has been variously given as The Sound of Silence and The Sounds of Silence. I believe the singular version was Simon’s title of choice.

Review of A Voyage to Arcturus by David Lindsay

Back in the 1970s, I read a strange, captivating novel called A Voyage to Arcturus. I recently reread it, and it seemed appropriate to give my thoughts on a book that few readers nowadays seem aware of, even though it’s been immensely influential.

The title would lead to the assumption that this is SF — and it is, in a way, but only to the same extent as C.S. Lewis’s space trilogy. And, in fact, Lewis was strongly influenced by it. In reality, this is a glorious but bewildering mixture of SF, S&S, religious allegory, surrealism and philosophical tract.

David Lindsay wrote the book in 1920, his first novel at the age of 44.1 Like a great many people at the time, he’d been traumatised and disillusioned by four years of war, in which he’d served in the army. His disillusion, indeed, seems a close parallel to Hitler’s, but Lindsay used his as a creative force, rather than a destructive one.

The novel begins in familiar territory, with a contemporary (i.e. 1920) scene in London describing a high-society séance.2 We’re introduced in a fair amount of detail to a range of characters who disappear after the first chapter, before two outsiders arrive — a large man called Maskull, and a smaller man called Nightspore.

After the séance goes wrong, it’s gate-crashed by a strange, uncouth man called Krag, who takes Maskull and Nightspore away and tell them they must journey to Arcturus. This is achieved from a remote Scottish observatory, in a capsule powered by rays from Arcturus that seek to return there.

Having passed out on the way, Maskull wakes to find himself alone of the planet Tormance, which orbits Arcturus, with no trace of his two companions. It’s a strange world. There are two suns — a normal, though larger and hotter, one called Branchspell, and a mysterious blue sun called Allpain, which can only be seen from the far north.

Tormance has many unique features, including two extra primary colours, called ulfire and jale, entirely unlike any colour on Earth. These appear, along with blue, to form the spectrum of Allpain, while Branchspell’s spectrum is the normal one.3

The landscapes of the planet are varied and bizarre, as are the flora and fauna. The water is, in many places, dense enough to walk on, while another type of water is a complete substitute for food. Mountains are piled up in impossible configurations, plants often walk about, while in one region Maskull witnesses endless new lifeforms coming into being as he watches.

When he starts to meet the inhabitants of Tormance, they’re equally strange. Most have extra organs, ranging in different regions from the poign, which enables understanding and empathy, to the sorb, by which one person can control another’s will. And one companion Maskull meets is of a third sex — not a mingling of male and female, but something as entirely separate as the colours. Lindsay coins the pronouns ae, aer and aerself to refer to this person.

Maskull travels through various lands on Tormance. This is partly from curiosity and partly a desire to see the blue sun Allpain in the far north, but also in search of a mysterious figure called Surtur. This person may or may not be the god of Tormance, otherwise called Crystalman or Shaping. Different Tormance cultures have a variety of views about this.

Maskull’s journey — meeting a range of philosophies, from ultimate love and altruism to a compulsion for dominating others, and being strongly influenced by each as he goes — has superficial similarities to Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, but this is no comfortable religious allegory. Where Bunyan clearly labels the significance of his places and people, Tormance remains a puzzle to be struggled with.

From strong attraction at the beginning to a philosophy of non-violence, Maskull is quickly seduced away. His trail is eventually littered with bodies — some he’s killed himself, others he’s failed to protect. He also has relationships with a number of women — none of whom survive the encounter.

Finally, now weary of life, he meets up again with Krag, who he’s heard described as Tormance’s Devil, along with an affable man who proves to be Crystalman. Maskull eventually comes to see Crystalman, the god of pleasure and the material world, as a corrupter who turns the spark of life into grossness, while Krag constantly challenges the desire for pleasure.

As Maskull dies, Nightspore re-emerges, and we’re left with the assumption that he’s actually Maskull’s soul. It’s Nightspore who’ll go on, helping Krag in his fight.

A Voyage to Arcturus is a captivating book, but not an easy one. For one thing, Lindsay’s postwar vision is incredibly bleak — the world is corrupt and evil, as is the God worshipped in it, and only by holding onto the tiny uncorrupted spark of life within can anyone have a hope in the struggle of life.

The meaning we’re supposed to take from it is also difficult to define. This is no obvious allegory, and we have to pick through the many philosophies put before us if we hope to get an inkling of its meaning. As Tolkien, who loved the book, said, “no one could read it merely as a thriller and without interest in philosophy, religion and morals”.

The novel has its faults, too. The prose is often clunky, though the lushness of the descriptions largely compensates for that, and the characters are curiously undeveloped. Even Maskull — although we have occasional vague references to dissatisfaction with his life on Earth, we’re told nothing whatsoever about that life. Not even how he knows Nightspore.

The book’s attitude to women isn’t entirely in line with modern standards, as might be expected from something more than a hundred years old, although it’s far better than some from the period. In fact, it isn’t easy to pick out the author’s views from those of the many philosophies Maskull encounters. Some of these are deeply misogynistic, but on the other hand most of the female characters seem to have more agency than their male counterparts.

In spite of its faults, A Voyage to Arcturus is a compelling book that won’t easily let go of you once you’ve read it. Although a commercial failure at the time (fewer than 600 copies were sold of the first press run), many authors have admired and been influenced by it.

Besides Tolkien, C.S. Lewis described it as “shattering, intolerable, and irresistible” and acknowledged it as a major influence on several of his own works.4 Michael Moorcock considered that “Few English novels have been as eccentric or, ultimately, as influential”, while Philip Pullman and Clive Barker have both praised it.

A Voyage to Arcturus is anything but light reading, and some readers will certainly find it too much. If you love philosophical conundrums along with the action, though, I’d certainly recommend following Maskull across the landscapes of Tormance.

1 The introduction to the edition I have (Pan/Ballantine, 1972) erroneously describes Lindsay as a “young forgotten writer” who “died young”. In fact, he died in 1945, aged 69 — not old, maybe, but not particularly young.

2 It’s quite an unusual séance, and I suspect Lindsay didn’t actually know what went on at séances, just inventing it to serve his purpose.

3 Lindsay does make an error with the “normal” spectrum, describing it as red, yellow and blue, even though he’s talking about the light of Branchspell.

4 Most notably his “space trilogy” (Out of the Silent Planet, Perelandra and That Hideous Strength), but also The Screwtape Letters.

A Fantasy World That’s All Grown Up

There’s a very clear traditional idea of what a fantasy world is supposed to be like. It has warriors riding horses and wielding swords and axes. It doesn’t have them travelling on planes and operating computers. It just doesn’t.

But why not? After all, our world has had all that and much, much more, at various times and locations. So why does a secondary world have to be frozen like a fly in amber? Sooner or later, all worlds have to grow up.

The Mediaeval World That Fantasy Isn’t

Perhaps the most widespread fallacy about fantasy secondary worlds is that they’re all mediaeval — by which people normally mean simply that they have horses and swords. In fact, “mediaeval” is a very specific range of cultures, relating to Western Europe between 732 and 1453 AD.1

Even so, customs and norms varied considerably between those dates and in different parts of Europe, but two crucial features can be picked out that define the era. One was the feudal system. The other was the unique position of the Church.

There are fantasy novels set in a genuinely mediaeval-style culture, of course. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series is perhaps the most obvious, as well as William Morris’s works like The Well at the World’s End. However, they’re very much in the minority.

Consider the various societies portrayed in Lord of the Rings, for instance. The Shire is essentially rural 19th century England without gunpowder (apart from fireworks); the Dwarves are Vikings; Rohan is very early Anglo-Saxon, as portrayed in Beowulf; and Gondor is perhaps more like ancient Babylon than anything. Then there are other societies, such as the Elven kingdoms and Mordor, that have no particular historical model.

In fact, a more typical kind of fantasy world (especially when it comes to sword & sorcery) most closely resembles the world of Classical mythology. A world where rootless heroes wander between tiny kingdoms whose constitutional arrangements are sketchy, to say the least, and whose religions mostly seem to involve sacrificing beautiful virgins. For all its faults, the mediaeval Church tended not to do that.2

Fantasy in the Modern World

There’s always been fantasy set in our own contemporary world, of course, but secondary world fantasy has tended to be, if not mediaeval, certainly pre-gunpowder. There have been slight exceptions. In Andre Norton’s Witch World series, for instance, she goes as far as to give Witch World warriors dart guns, but there’s also futuristic tech — although it’s been brought in from outside their world.

More recently, though, some fantasy authors have been experimenting with different kinds of settings. That’s often been to do with a less Eurocentric focus, but some settings have been post-gunpowder, or even societies with similarities to the modern world.

The New Weird movement, whose best-known exponent is China Miélville, mixes genres. It typically employs invented urban fantasy settings, often with modern or steampunk overtones, but featuring a wide range of fantasy races and themes. In Miélville’s world of Bas-Lag, for instance (as featured in Perdido Street Station and other novels) dozens of strange and wonderful types of sentient beings coexist with railways and other Victorian-level technology.

One of my favourite examples of this movement is Mary Gentle’s Rats & Gargoyles. This is set in a vast city (we’re told it spreads over several time zones) which initially seems very much like a classic fantasy city, apart from being ruled by human-sized rats. As the story unfolds, though, we gradually realises that it actually possesses a wide range of modern technology.

Letting Worlds Grow Up

When I started writing stories in what was to become the Traveller’s World, it was very much a classic fantasy world. Right at the beginning, in fact, I was referring to characters as knights, and there was more than a hint of Arthurian legend about it, although this quickly morphed into something closer to classical Greece.

Quite early, I found my way to using different parts of the world and widely separated time periods, but they were all essentially pre-tech. I did allow a little progress, though at my own preferred rate (they had the printing press before gunpowder, for instance), but essentially it remained an “ancient” world.

Then, about twenty years ago, I began to reconsider. It occurred to me that, logically, at some point much later than anything I’d yet written, this world too would “grow up”. I began to wonder what this “modern” world would make of the major legends of its past, such as the Traveller.

The first fruit of this line of thinking was a story called Present Historic, in which a “modern” diplomat is inspired to pursue international cooperation by legends of the Traveller — which now appear as films and comic books. This idea fascinated me. Although I continued (and still continue) to write plenty of stories in “classic” settings, I began exploring this new, grown-up Traveller’s World.

Not all the settings are entirely modern. One is what I call “flintlock & sorcery” (a kind of fantasy equivalent of The Three Musketeers), while others are set in a gaslight era. Many, though, are set in a period that features equivalents of smartphones and PCs — and a few are even slightly in advance of our current level of progress.3

I’d already established, in the classic fantasy, that the Traveller’s World isn’t so very different from ours. It doesn’t have six moons, or bizarre sentient beings living side by side with humans (well, not many, at least), and I extended this into the modern era. Overall, the societies and their technologies have developed in ways similar to ours — though with certain differences. Cars are all electric, for instance, planes are VTOL, and you “dial up the vidscreen”, rather than turn on the TV. Broadly, though, it’s much the same.

Just like much contemporary fantasy set in our own world (especially paranormal fantasy) the predominant theme in these stories is the effect of the supernatural traditions of the past on a rational, sophisticated society. Here, it can be anything from people trying to revive worship of the Demon Queen or the Great One (the global power of evil) to finding remnants of ancient, paranormal races.

How Far Can a Secondary World Go?

So I have stories set in various iron age societies of the Traveller’s World (the comfort zone for fantasy) and also stories set in its “early modern” and “modern” eras. But are there are other periods that would work? How far can a secondary world go?

Well, possibilities do exist. I have a couple of stories set in the bronze age, for example — but there are limits. If I wanted to write stories about palaeolithic hunter-gatherers, for instance, what would distinguish it from a story set in that era of our world?

We know nothing really of the cultures or languages or beliefs from that far back, and the characters wouldn’t have names for the countries or areas they live in. Unless the secondary world had something quite distinct (those six moons, for instance), there’d be no difference between a story set in the forests of northern Europe and one set in the great Kimdyran Forest.4

Curiously, the same applies if you go too far beyond a “contemporary” setting. There’s certainly room to get a little futuristic, but when the people of the Traveller’s World start boldly going where no man has gone before, the universe they explore could just as well be the universe our descendants might explore.

Some heritage elements could be brought in, of course. Some of the cities back home might be the same, and a pioneering starship could be named Searcher, after the Traveller’s vessel. But these would be largely cosmetic elements. There’d be little true reason for the story being set in a secondary world.

So, it seems, the useful life of a secondary world is from the end of the stone age to the beginning of the interstellar age. Which leaves plenty of room to explore, whether your tastes run to sword & sorcery or to urban fantasy. Or both.

So have fun.

1 There are various reasons for singling out the Battle of Tours in 732 as the beginning of the Middle Ages, but the principal one was that it began the supremacy of the knight as a fighting force, with the feudal system that came along with it. The fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453 was significant in itself, but it also marked the point where all the major features of the early modern era were under way.

2 Unless you count burning heretics at the stake, of course.

3 An example of this is a story called Tattered Wings, in which even a fairly low-income family lives in a house with voice-activated lights and other systems.

4 I actually do have a palaeolithic story set in the Traveller’s World — but only because I say so. It could just as well be set in our prehistory.

The Aryan Fallacy

Note: This is an updated version of a post on my old blog from 2015. Recent events suggest that it may need saying again.

In 1938, J.R.R. Tolkien received a letter from a German publisher who proposed to publish a translation of The Hobbit. According to the laws under the Nazi government, they requested him to confirm that he was “of Aryan origin”.

Tolkien was livid. He made his opinion clear in a related letter to his British publisher, where he said, “I have many Jewish friends, and should regret giving any colour to the notion that I subscribed to the wholly pernicious and unscientific race-doctrine.”1

In his reply to the German publisher, he feigns innocence at first. “I regret that I am not clear as to what you intend by arisch. I am not of Aryan extraction: that is Indo-iranian; as far as I am aware none of my ancestors spoke Hindustani, Persian, Gypsy, or any related dialects.”2

Tolkien had no truck at all with the Aryan Fallacy, but many of his contemporaries embraced it enthusiastically, including several other fantasy writers active at a similar time — very notably Robert E. Howard. So how did it come about?

The Original Aryans

The word Aryan (or more strictly Arya) correctly refers to a group of nomadic tribes that moved into northern India about three to three-and-a-half thousand years ago. In fact, there’s evidence that it didn’t originally refer to an ethnic group at all, but to a culture — and, more specifically, to a status within this culture. Many of the kings defining themselves as “Arya” appear to have been indigenous rulers who’d adopted the ways of the newcomers. This parallels the way that diverse peoples from all over the Roman Empire became “Romans” by learning Latin, adopting Roman names and following Roman customs.

The term Aryan is also used for the linguistic family descended from Sanskrit, deriving ultimately from the language(s) spoken by these tribes and their converts. Lastly, and with extreme caution, it can be applied to the people who speak these modern languages (most of the languages of Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, northern and central India, and the majority language of Sri Lanka). As long as it’s understood that this in no way represents a racial identity.

The family, as Tolkien indicated, also includes Romani (“Gypsy”), its original speakers having migrated from north-west India. Ironically, in Hitler’s time (i.e. before the mass migrations from the sub-continent after World War Two) the only substantial ethnic group in Europe who could legitimately call themselves Aryan were the Romani — who were persecuted by the Nazis.

The most obviously related group of languages is the Iranian family, together forming the Indo-Iranian group (Iran derives from the same root as Aryan). Today, the Iranian group covers most languages of Iran and Afghanistan, together with Kurdish, but in earlier historical periods Iranian-speaking nomads lived on the steppes north of the Black and Caspian Seas: Scythians, Sarmatians, Alans etc.

The Origins of the Fallacy

In the late 18th century, linguists began to recognise a clear relationship between the earliest forms of Sanskrit, Greek and Latin, and postulated that they might all have derived from a common source. With this leverage to build on, the Germanic, Celtic, Slavonic and other language groups were added to the growing super-family, nowadays known as Indo-European. An extinct family of Indo-European languages, Tocharian, was even spoken in north-west China during the Han era.

In the 19th century, it was proposed that the whole family should be called Aryan, in the erroneous belief that this was the earliest name of a people speaking an Indo-European language3 and therefore the most likely to be the original.

Though mistaken, this was originally innocuous, but a tide of racial supremacism gradually saw the label become more and more equated with the “German Race”. The concept was that the “original Aryans” had been white, blond and blue eyed, but had subsequently mixed with “lesser” races. In fact, the reality is more likely to be the opposite — the lighter colouring evolved from living in a colder climate.

Max Müller, one of the originators of the original proposition, was later scathing about colleagues who confused linguistic and racial characteristics, suggesting that “Aryan race, Aryan blood, Aryan eyes and hair” were as absurd as “a dolichocephalic dictionary or a brachycephalic grammar”.4

The tide was against him, though, and the concept of the Aryan Master Race became more and more widespread, eventually finding its lunatic home in the warped mind of Adolf Hitler. In fact, there have been suggestions that the characteristic differences between the Germanic languages (including English) and all other Indo-European languages may have been the result of an unrelated people abandoning their own language and taking up a broken form of Indo-European. In which case, the Germans have even less right to the name Aryan than most other Indo-European speakers.

The Indo-European Language Family

The clear pattern of divergence among the languages through various periods has always suggested that it should be possible to trace them all back to a time when a single language, from which they are all descended, was spoken by a community in a relatively small area. The favourite explanation nowadays is the steppes of south-eastern Europe somewhere between 4500 and 2500 BC, but other propositions have ranged from the eccentric (such as the North Pole) to the vaguely plausible (such as Anatolia or the north-western European plains).

It shouldn’t be assumed, though, that these original Indo-Europeans represented a race, or even a “people” as we’d understand it. Archaeological evidence suggests that the communities who probably spoke Indo-European were actually made up of several distinct groups — a people who’d come down from the north, another who’d come up from the Mediterranean, and possibly others from Central Asia or the Caucasus — who can all be seen from their remains to have been very different physical types.

Nor are they likely to have had much in common, including political or tribal structures, except the language which allowed ideas and customs to spread. They constituted a culture area, but no more.

In terms of the later spread of Indo-European, too, we can’t assume any racial connection. It’s not unusual for peoples to adopt the language of either the dominant or the “cool” culture, and this often means communities speaking a language aren’t racially connected with the those who spoke the language’s distant ancestor. If we didn’t accept this, we’d have a hard time trying to explain how an English-speaking African American could have derived from the language’s source in north-western Europe.

The subsequent evolution of the languages is likewise anything but straightforward. Linguists use the family tree model (e.g. Latin is the “parent” of French, Spanish, Italian etc.) and this is useful, but the influence of other, often unrelated languages is important too. This can be down to extensive borrowing of vocabulary for social or political reasons, such as how English, fundamentally a Western Germanic language, has a vocabulary heavily derived from Latin.5 It can also be explained, though, by the wave theory of language change.

The wave theory is a model which suggests that specific changes, whether a sound-change such as a final t changing to s or a grammatical change such as the development of grammatical gender, spreads from an epicentre and affects both related and unrelated languages. The next major change will have a different epicentre, and/or the speakers will have moved, so it won’t be the same set of languages affected.

Ultimately, this will create a patchwork, in which it can be difficult to reconcile a language’s position on its family tree with apparent similarities to more distantly related (or unrelated) ones. It’s inconvenient, but we’re talking about human behaviour. What do you expect?

Tracing the Story Further Back

So where did the original Indo-European language come from? If it was being spoken a mere five or six thousand years ago, it obviously can’t have sprung from nowhere. The reason it’s recognised as the “original” is that it marks the latest point that all Indo-European languages can be traced back to, but its history must have gone back a long way up an unknown family tree.

Various propositions have been made as to what Indo-European might ultimately be related to, the most widespread being a super-family known as Nostratic. At its most ambitious, this hypothesis includes Uralic, Altaic, Kartvelian, Afroasiatic, Elamo-Dravidian and Eskimo-Aleut, along with a few others, though some more cautious proponents restrict it to the first three plus Indo-European.6

There’s very little evidence for hypotheses such as this, and what has been put forward is strongly disputed. The problem is that it becomes progressively harder to be sure of similarities between languages the further back the proposed connection is. It’s probable that some, at least, of these language groups actually are linked, but nothing’s likely to ever go beyond speculation.

To speculate, though, how far might this process actually reach? Recent evidence suggests an origin for language considerably further back than was believed even a decade or two ago, certainly back to when our ancestors were living in a fairly small area of Africa.7 Maybe the invention of human language really was a single event, and we’re all speaking variants of the same language. Just as all humans have the same origin.

The Aryan Fallacy should have died in the bunker with the Führer, but unfortunately bigots aren’t famous for their intellectual rigour, and there are still white supremacist morons who use it as a keystone for their disgusting creeds.

So take a leaf out of Tolkien’s book. Next time a white supremacist proudly claims to be Aryan, point out that they’re actually claiming to be Indian. Or even Iranian. You won’t change their views, but see how they like it.

1 The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, ed. Humphrey Carpenter, 1981, p.37

2 Ibid. p.37

3 To be fair, this was a reasonable belief at the time, but earlier examples have been found since then, including the Hittites, who dominated Anatolia during the later Bronze Age.

4 Quoted in In Search of the Indo-Europeans, J.P. Mallory, 1989, p.269

5 That the roots of English are Germanic can be illustrated by taking a passage of average English and identifying where each word came from. It’s likely that more would be Latin-derived than Germanic-derived; but if you were to redo the exercise counting each word each time it’s used, you’d find the count overwhelmingly Germanic. This is because the most common, infrastructure words (the, and, to, for and the like) are direct descendants of the words that came over with the Anglo-Saxons.

6 Uralic includes languages like Finnish and Hungarian; Altaic includes the Turkic languages, Mongolian, probably Korean and possibly Japanese; Kartvelian is a small group whose main member is Georgian; Afroasiatic is a huge group, ranging from Hebrew and Arabic to Hausa, the main language of northern Nigeria, and taking in ancient Egyptian along the way; Dravidian was the main language group in India before the coming of the Aryans, and is still dominant in the south; Eskimo-Aleut — yes, I know Eskimo is non gratis, but there’s actually no other word for the whole linguistic group, the Inuit actually being just the largest ethnic group.

7 Remains have indicated that Neanderthals shared the same deformity of the larynx that allows us to manipulate complex sounds, suggesting that the mutation took place at least 150,000 years ago, probably earlier. On the “use it or lose it” principle of evolution, it’s difficult to interpret this any way other than our ancestors already using language from that point.

Doctor Who Series 1 — or Series 14 — or Series 40

The most recent series of Doctor Who finished a couple of weeks ago. Due to Disney’s dictates, it’s officially described as Series 1, which has angered a lot of fans, who insist that it’s actually Series 14. Whereas, as us old-timers know, it’s really Series 40.

Whatever it’s called, though, I’ve now had time to rewatch and consider it, so here are some thoughts.

Overall, I enjoyed this series, although I do have some criticisms. Those don’t, though, include Ncuti Gatwa’s interpretation of the Doctor, which I like, and he and Millie Gibson as Ruby have shown excellent chemistry.

It’s always made sense to me that a regenerated Doctor would have the energy and enthusiasm of youth, rather than regenerating into a venerable elder (much as I’ve loved many of the venerable elder Doctors). Ncuti captures that perfectly, without sacrificing the feel of the millennia making up the Doctor’s past.

Of course, there have been accusations of “wokeness” from the usual suspects. I’ve always found “woke” a ridiculous word to use as an insult — how dare they actually be awake to things, instead of burying their heads in the sand? In any case, in practice it’s just a way for bigots to have the illusion of a moral high ground for their bigotry — in this case, especially about race and sexuality.

In any case, Doctor Who has never shied away from tackling important issues while it’s telling exciting stories. It first tackled racism in 1963 and did the first of many ecological stories the following year, while the two Peladon stories of the early 1970s directly (and not even very subtly) mirror political events in Britain at the time.

So what about the individual episodes?

WARNING: HERE BE (a few) SPOILERS

Episode 0 — The Church on Ruby Road

Actually the Christmas special, but it sets up the main recurring elements of the series, so should really be treated as part of it.

This does a good job of introducing the new Doctor and new companion, both to us and to each other. The goblins seem a bit left-field for Doctor Who, but I did like the way the Doctor described the “magic” as an alternative science — it reminded me of the Third Doctor story The Daemons.

What I didn’t like here was the musical number (although it’s better than what comes later) which seems like something straight out of Labyrinth. Now, I love Labyrinth, but what works there doesn’t necessarily work in Doctor Who. We had a musical number in The Giggle and there’s another later — enough.

The main threads set up here are the mystery of Ruby’s mother and the enigmatic neighbour Mrs Flood. The former is central to the story, while the latter is only hinted at in the final line of the episode. And we also have a brief, seemingly irrelevant appearance by the mysterious woman who follows the Doctor and Ruby throughout the series.

Episode 1 — Space Babies

This episode has got a fair amount of stick, and I’ve even seen it described as one of the worst Doctor Who stories ever. Well, it’s certainly no classic, but it’s also nowhere near that bad.

Space Babies is fairly light and silly (and has several significant plot holes) but I found it enjoyable enough. An abandoned “baby farm” in space is being run by the equally abandoned babies, who for some inadequately explained reason are still physically babies but mentally older kids. They’re menaced by the Bogeyman — whose name turns out to be disturbingly literal.

It’s technically very clever in the way it creates a convincing illusion of the babies speaking, and it gives the Doctor and Ruby more opportunity to bond, but as a story it’s rather throwaway. No worse than that, though.

Episode 2 — The Devil’s Chord

This seems like a great idea. The Doctor and Ruby go back to 1963 to watch the Beatles recording their first album, only to find that a malevolent power called Maestro has stolen all the music in the world. All the Beatles can muster up is drivel that wouldn’t even work as advertising jingles.

Somehow, though, it doesn’t quite gel. Maestro (played by drag artiste Jinkx Monsoon) is spectacular, although arguably too overpowering, but the Beatles themselves are not only underused, but also very poor as lookalikes. And, at the end, the whole thing dissolves into what can only be described as a music video that has nothing to do with the story — and isn’t even musically appropriate.

Perhaps the most interesting scene is where the Doctor tells Ruby that, at this time, he was living in east London with his granddaughter. This helps set up the finale and may well be relevant beyond the series.

Episode 3 — Boom

The first episode written by Stephen Moffatt since laying down the reins, and it’s an absolute stonker. Everything that makes a great Moffatt episode great: an unexpected situation, tension and drama, complex moral issues, great relationships, and a well-written, well-acted kid.

Briefly, the Tardis materialises in the middle of a war on a planet involving the Anglican Marines we’ve seen a number of times in the past, and the Doctor steps on a sentient land-mine. He has to find a way of getting away without setting it off, which would destroy half the planet — and stop the AI from “ambulance” killing everyone in the name of profit for its manufacturers.

If Space Babies represents the show at its most frivolous and childish, this is Doctor Who at its most grown up, exploring a relationship between war and capitalism that’s absolutely relevant to our own world. A very limited set and small cast, but a superb episode.

Episode 4 — 73 Yards

It’s unexpected to have a Doctor-lite episode so early in the run (it was apparently to do with Ncuti’s remaining commitments elsewhere) but it’s one of the more successful ones. In some ways, it’s a little reminiscent of Turn Left, showing the companion in an alternative timestream without the Doctor — but this one going forwards instead back.

Millie Gibson as Ruby does an excellent job of holding together a story that moves through many different time periods and a constantly changing cast. Along the way, she encounters a bunch of weird locals in a Welsh pub, meets Kate Stewart, and stops a terrifying prime minister from starting a nuclear way — all the time followed by a strange woman who’s always exactly 73 yards from Ruby and turns anyone who makes contact against her.

None of this is really explained, although an explanation of why it’s 73 yards is suggested in the series finale. What’s caused it? The Doctor breaks a fairy circle, but is it really magic, or is something else going on? Who’s the woman, and what does she say to people? It’s possible to make guesses about what’s going on, but on the whole it’s left a delicious mystery.

Episode 5 — Dot and Bubble

The initial premise of this story reminded me a little of The Macra Terror from 1967 — a relentlessly hedonistic society resolutely ignoring the fact of being menaced by monsters. However, the two stories are radically different, both in the nature of the society and in the way the idea develops.

A number of people have pointed out this is a rather Black Mirror type of story, with social media gone to the ultimate extent where people spend their entire lives surrounded by a virtual bubble and never interact directly with anyone. And this proves to provide the specific reason why the monsters have begun preying on them — in alphabetical order.

The Doctor and Ruby take something of a back seat here, and we follow a character called Lindy who, like everyone in the society, is a spoilt, overprivileged rich brat. She starts off annoying and ends up off-the-scale nasty, and it’s a tribute to the writing and acting that we’re able to stick with her for most of the way. And the Doctor’s reaction, when he realises these people would rather risk their lives than let a black man help them, is spine-tingling.

The biggest downside of this episode is that the monsters themselves are physically a bit rubbish. Fortunately, though, it’s not a story that relies on monsters for its effect.

Episode 6 — Rogue

Basically, this is Doctor Who does Bridgerton — and, if that weren’t already obvious, Ruby makes a number of references to the fact. Set at a high society ball in 1813, it goes wrong when shapeshifting (or “cosplaying”) aliens start killing the guests. And then an extraterrestrial bounty hunter, called Rogue, arrests the Doctor on suspicion of being the killer.

Rogue reminds me a little of Jack Harness when he first met the Doctor, but this goes further. It’s pretty much love at first sight, and we’re teased with the possibility of an ongoing romance in the Tardis — until Rogue sacrifices himself to save Ruby. Not dead, but lost — which dangles the opportunity for the Doctor to find him again.

The interactions between the Doctor and Rogue are beautiful and moving, and the costumes and dancing are stunning, but the one slight weakness is the shapeshifters themselves. They’re menacing when preying on the humans, but their bickering between themselves comes over as a little silly, a bit reminiscent of the Slitheen. But that’s really the episode’s only weakness.

Episode 7 — The Legend of Ruby Sunday

For the beginning of the two-part finale, the Tardis arrives at UNIT headquarters (flying rather than materialising — why? There’s been far too much of that lately) so the Doctor can enlist the help of Kate and co (including Mel and Rose Noble) to unravel the twin mysteries of Ruby’s mother and the mysterious woman who’s turned up everywhere they’ve materialised.

They tackle the former by using UNIT’s “time window” to examine the church on Ruby Road (since the Doctor can’t take the Tardis back without blowing up the universe). The mother’s identity continues to elude them, but the window reveals a destructive entity around the Tardis.

Meanwhile, Mel investigates the mystery woman, who proves to be a tech billionaire called Susan Triad — and, since S Triad is an anagram of Tardis, the Doctor begins to suspect she’s his granddaughter Susan, mentioned earlier in the series. There’s a curious little exchange with Kate where he reveals that, although he has a granddaughter, he doesn’t have children — yet. The life of a Time Lord.

In fact, she proves to be the harbinger for the entity — Sutekh, last seen in 1975’s Pyramids of Mars and for a long time joint top (along with the Toymaker) of my wish-list for returning classic enemies. The end of a brilliant episode sets up the climax perfectly.

Episode 8 — Empire of Death

It’s happened a few times that the penultimate episode sets up the finale brilliantly, and then the final episode doesn’t quite deliver. This is one. Not that it’s a bad episode, just that it aims high and falls a little short. Perhaps it collapses under its own weight.

The best thing about it is Sutekh, voiced wonderfully as he was 49 years ago by Gabriel Woolf. We find that Sutekh escaped his fate by attaching himself to the Tardis and travelling invisibly with it ever since. That’s a bit of a stretch, considering how events happened in Pyramids of Mars, but I’ll buy it. And his upgraded appearance is explained by fifty years in the time vortex. Again, I’ll buy it — he looks superb.

Sutekh destroys all life, not only on Earth, but also everywhere and everywhen he’s been with the Tardis. It turns out that Susan Triad was a personality generated every time the Tardis materialised, and every version of her is Sutekh’s harbinger.

The Doctor, Ruby and Mel go on the run, and eventually trick Sutekh, managing to destroy him in vortex. And, somehow, this reverses everything he’s done and brings everyone back to life. Why? I’ve no idea.

Which leaves the resolution of Ruby’s mother — who turns out to be just an ordinary woman who had a baby she couldn’t cope with at fifteen. I kind of like that she isn’t anything cosmic, but it doesn’t really explain why so much freaky stuff happened around her, or why Sutekh was so obsessed with her as to break his cover. It just didn’t make sense to me.

The Future (Or Is It the Past?)

So what’s the future for Doctor Who? I feel that Ncuti Gatwa has made a great start as the 15th Doctor, though there seems to be plenty more to come. He brings something new to the role, without sacrificing the character’s long heritage.

Ruby left the Tardis at the end of the last episode, wanting to concentrate on her newly found birth parents, though it seems she’ll be appearing in some of the episodes in the next series — rather as Martha did. The new companion is going to be played by Varada Sethu, who was Mundy Flynn in Boom. It’s not clear whether she’ll be the same character or join the long list of Doctor Who actors who’ve played someone different before becoming a recurring character.

Personally, I’d like to see a different kind of companion. Although there have been exceptions, most NuWho companions have tended to be contemporary girls or young women who fit the “manic pixie girl” type. While a lot of classic companions fitted that description too, there were also plenty of non-terrestrials, or characters from the past or future. I’ve always thought a perfect companion would be one of the “domesticated” Zygons we met back in 2015: thoroughly familiar with contemporary culture, but with an “outsider” perspective.

And then there are the enemies. It’s notable that Russell T Davies avoided the obvious for this series — no Daleks, no Cybermen, no Master. I doubt if we’ll get through another series without any of them, and that’s quite right and proper. At the same time, he’s introduced new enemies and brought back some less obvious ones.

I referred earlier to my wish-list of classic returners. There are lots I’d love to see again (given an appropriate story, naturally) but top of the list would be the Rutans, age-old enemies of the Sontarans. We’ve only ever seen them once (in the excellent Horror of Fang Rock) and never facing off against the Sontarans. The Rani, the Monk and Omega would also be very welcome, and it would be good to see the Mara (or a Mara) again.

There are several ongoing plotlines to take into the next series. The Doctor has suggested he wants to search for Susan, having thought he might have found her and been disappointed, and there’s always the possibility of finding Rogue again. And Mrs Flood’s story is far from told — whoever she might turn out to be.

In spite of the latest crop claiming Doctor Who is being destroyed by this or that (as successive voices have been saying for decades), I’m looking forward to series 2. Or 15. Or 41.

Who Wants to Live Forever?

About forty years ago, I wrote a short story exploring the idea of immortality. The main character (a kind of everyman — or everywoman in this case) does a favour to a supernatural being who, in gratitude, offers to make her immortal.

As she’s a bit unsure what to make of this, he takes her to meet two men he gave the same gift to thousands of years before. One turns out to be sunk in misery and boredom, mourning for lost people and longing for his ordeal to end. The other is full of enthusiasm, remembering the people who’ve gone but welcoming new people and new ideas.

The point I was trying to make, of course, was that it was really nothing to do with immortality. The two characters reacted as they did because of the kind of people they were, and that would have been true however long or short their lives had been.

The story was never published, and rightly so, as the plot and characters were too formulaic, just excuses to make a point. But I’ve written plenty in the intervening years about immortal characters, and the basic philosophical issues I raised forty years ago have had plenty of airing.

But what exactly is immortality? It’s not as straightforward a question as it might seem, and in my stories set in the Traveller’s world, I have three quite distinct types of immortal characters.

The Undying Mortal

Most of my immortal characters, notably the Traveller, fit into the “undying mortal” category. These are people who have started out as ordinary humans but, one way or another, have stopped aging or decaying.

There are various magical or supernatural methods by which this happens, but really I’m not especially interested in that aspect. Although the various incidents may be vivid or exciting, they’re really just excuses to explore immortality.

Although in general the people involved have no idea what’s happened to them, I have established for myself how it works — and this model is actually discussed in an as-yet-unpublished story from the “modern” era, where human physiology is understood. It’s not that I’ve worked out how to make it happen, of course (I’d be rich if I had), but I do have a reasonable model of what happens on a physiological level to someone undergoing the process.

It’s actually quite simple. The physiology is altered so that each cell is constantly “resetting to default” — that is, to the exact state it was in when the change occurred. This has various results, most obviously that the Traveller (and others) don’t deteriorate at a cellular level. This includes, for instance, that there’s none of the shortening of telomeres that’s associated with aging. On all levels from outward appearance to each individual cell, you would remain the same as when the change first occurred.

There are other implications. It makes the body more resistant to disease and hastens healing of wounds — although neither of these is infallible. If the Traveller were stabbed through the heart, he’d still die. Perhaps crucially, though, the process prevents cancers from developing. In practice, anyone living for centuries, let alone millennia, would eventually develop cancer, but the first hint of a cancerous cell would get zapped back to its default.

There are holes in this process, though. I can’t really explain why the same process wouldn’t apply to the neural network — and, come to that, the capacity of an immortal’s brain seems to be infinitely expandable. Of course, I have the get-out-of-jail card that we don’t really know how a young, healthy brain would react to living for thousands of years. And, since this isn’t science fiction, that excuse will do.

The Immortal Gods

I haven’t really introduced the gods much in any published works, though this is intended to change. They’re a completely different type of being from mortals, although they actually know very little about their own nature. For the most part, they believe their own mythologies, even though many of them are mutually exclusive, and there’s a suggestion they may have been created by their worshippers’ faith.

All the same, their nature is very consistent. Their physical form is entirely different, and I’ve played with the idea of it being based on a triple helix, instead of a double one. Whatever exactly that might mean. The most characteristic difference is that they’re visible by self-generated light, rather than reflected light — which means, most significantly, that they can be seen in the dark.

They’re also immortal in the sense of not being fully tied to their bodies. Even if the body is totally destroyed (as happened in one unpublished story) they can simply grow a new one. Though, for it to be viable, it has to “look like” the particular god.

Unlike the “immortal mortals”, the gods are immortal because death has nothing to do with them. That doesn’t necessarily mean they last forever, though. The gods are intimately linked to their worshippers’ belief and faith, and if no-one believes in a god any longer, they go mad and eventually disappear. No-one knows what happens to an ex-god.

The Maverick

There’s always one who doesn’t fit in, isn’t there? My maverick immortal is called Renon, who appears in At An Uncertain Hour and in a number of not-yet-published novels and short stories.

Renon is a strange figure, who wanders in and out of various times and places, nudging events in the direction he insists they need to go. Although his appearances cover at least ten thousand years, that doesn’t necessarily mean he’s lived that long. He talks about “walking to tomorrow and yesterday” and appears to be more of a time traveller than an immortal.

Or perhaps he’s simply the author, who can visit any part of the story and adjust it to go in the right direction.

Living With Immortality

That forty-year-old story was written partly as a reaction to the common assumption that immortality would be a curse: that immortals would be either miserable, or else detached and amoral. Those are certainly possible reactions, and perhaps more true of the gods in my stories, but there are other alternatives.

Of the “undying mortals” in my stories, some certainly take those paths, or worse. They abuse and kill people, either because they don’t feel accountable or because beings that are here and gone aren’t worth worrying about. Certainly, the gods, even when not cruel, tend not to understand the real value of the mortals who worship them.

The Traveller, on the other hand, never loses sight of the value of other people. The past is important to him, but it doesn’t tie him, and he’s constantly eager to find something new. And there are new things to find, even after thousands of years, because the world is big, it’s changing all the time, and there are always new people, not quite like anyone else.

In the end, this isn’t really a question of lifespan, but about how you approach life. In that respect (though by no means in all others) I’m quite like the Traveller. I’ve lost many people during my life, either to death or just to change, and of course I miss many of them, but throughout my life I’ve always found other people to care about. And that’s precisely how the Traveller approaches his immortality.

It’s really about living in the moment, because the moment is the same, whether your life is twenty years or two thousand. The Traveller knows more than most that everything is transient:

“The only events we can call beginning or end are the moments of our birth and death, and even those are only absolute for us. Perhaps that is why death is so important, because what we do at the instant of death is forever.”

And knowing that he could, ultimately, die is what defines his life as much as ours — and what sets us all apart from the gods, who know nothing of death.

“The only events we can call beginning or end are the moments of our birth and death, and even those are only absolute for us. Perhaps that is why death is so important, because what we do at the instant of death is forever.”

And knowing that he could, ultimately, die is what defines his life as much as ours — and what sets us all apart from the gods, who know nothing of death.

Empires, Evil and Otherwise

You don’t have to travel far within either fantasy or science fiction before you trip over an empire. If anything, in fact, they’re even more prevalent in SF than in fantasy, from the empire of the Klingons and the one that strikes back to the enemies of the Foundation and of the Atreides. Most are evil empires (largely because we prefer to support the little people) but not all.

But what actually is an empire? And, just as importantly, what isn’t? It’s one of those words we all assume we understand, but actually the concept of an empire is an accident of history that’s not easy to pin down.

What’s an Emperor?

OK, surely the simplest definition is that an empire is ruled by an emperor. Or an empress, of course, though historically there have been very few regnant empresses. 1 As we’ll see, this is by no means always true — but it still begs the question of what an emperor is.

Surprising as it might seem, the title emperor actually started life as a military rank. The Roman rank of imperator (emperor is just the slightly mangled English rendering) was roughly equivalent to the modern field marshal, and most often referred to the commander-in-chief of the army under the Republic.

This was just one of the many positions of power accumulated by Augustus, the first Roman emperor, and passed on as a package to his successors. The full package gave Augustus control over virtually every aspect of Roman life — but it probably reflects the Roman psyche that it was the military rank that came to define his rule.

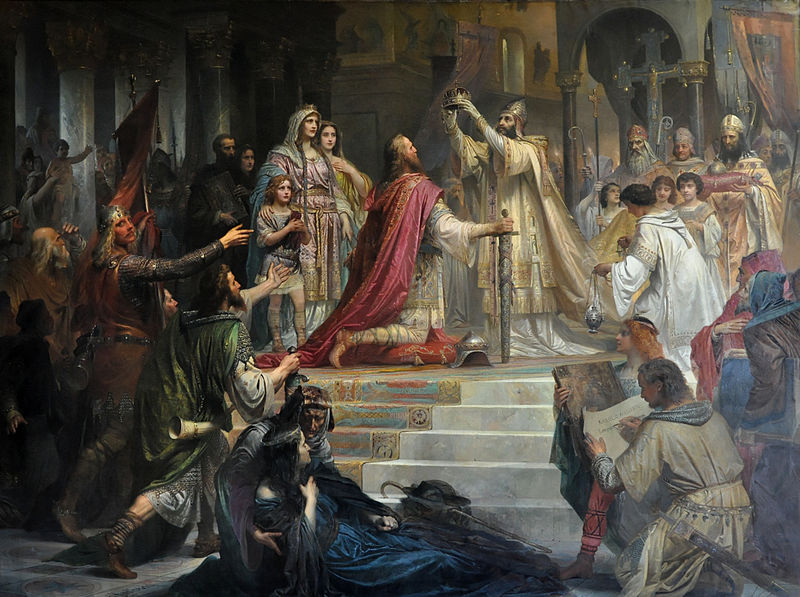

The last western Roman emperor, Romulus Augustus, abdicated in the year 476, although the line of emperors continued for nearly another thousand years in Constantinople. Much of later European history, though, consisted of attempts to revive the lost empire, and a whole series of rulers, starting with Charlemagne, had themselves crowned emperor in an attempt to identify themselves with the Caesars. 2

From Charlemagne down through the Holy Roman Emperors (a title that didn’t appear till the 12th century) to Napoleon and the Austrian and German emperors (and others from Spain to Bulgaria) all these were consciously trying to be the heirs of Augustus. In the east, the Russian emperors (styled tsar or czar) were similarly emulating the eastern Roman (or Byzantine) emperors. But what about emperors elsewhere in the world?

The traditional rulers of China (till the early 20th century) and Japan (ongoing) are conventionally referred to as emperors. However, the actual titles (Huangdi in Chinese and Mikado in Japanese) have names meaning Son of Heaven and Ruler from Heaven, respectively. 3 Neither has a trace of the military origins of emperor. And this is much the same for the “emperors” throughout Asia, Africa and the New World, from the Ottoman sultan to the Aztec huey tlatoani.

Empires Without Emperors

In fact, even if we take the attitude that all these titles are “close enough” to meaning emperor, by no means all empires have had a ruler with a special title. Many (the Persian and Macedonian empires, for instance) had rulers who simply used the same title as lesser kings. I have such an empire in my works. The ruler’s subjects call her the Queen, whereas her enemies call her the Demon Queen.

The British Empire never had an emperor, either. Victoria’s imperial proclamation in 1877 was specifically as Empress of India (in succession to the recently deposed Mughals), not as British Empress. Outside India, she was still a queen.

Empires don’t even need to have a monarch at all, whatever they’re called. The Roman Republic had effectively ruled an empire for a couple of centuries before Augustus. This was officially governed, like the city itself, by the Senate and Roman People, although this became increasingly nominal as a series of generals (Sulla, Pompey, Caesar, Augustus) seized effective power.

Another notable example of a republican empire was the Athenian Empire of the 5th century BC. This started life as the Delian League, an alliance of equals against the Persians, with Athens simply as the most powerful member. Gradually, however, Athens tightened its hold on its allies, to the point where they were punished with extreme prejudice for wanting to leave.

And that process continued. During the Cold War, arguably both the USA and the USSR had empires — neither ruled by an emperor or empress.

What Is an Empire — and What Isn’t?

Perhaps the most sensible approach would be simply to ditch the whole idea of emperors to define an empire. The previous section shows that we recognise an empire when we see it. So what defines it? And why are other political solutions that look similar not empires?

The simplest definition is that it’s an empire when one state, whether a kingdom or a republic, has gathered others under its control, whether by conquest, alliance or economic pressure. It’s a reasonable working definition — but not necessarily adequate.

After all, many modern nations originated that way, certainly in Europe and much of Asia, but we don’t regard them as empires. The Kingdom of England, for instance, later subsumed into the United Kingdom, was originally many kingdoms — 1200-1300 years ago, for instance, there were seven, though there had earlier been more.

They generally recognised a bretwalda (essentially a high king) who had seniority over the other kings without being officially their overlord, and eventually this passed to the kings of Wessex, including Alfred the Great. Gradually, through a process of conquest, marriage and liberation from the Danes, the Wessex kings evolved into kings of the English. 4 While that might have briefly seemed like an empire, this perception didn’t last.

Some nations, on the other hand, form as federal entities — such as the USA. While this model has some similarities to an empire, to the extent that it’s made up of a number of political entities ruled collectively, the difference is that no particular part of the whole has control of the rest. 5

So let’s adapt the working definition I gave above. Perhaps it would be more true to say that an empire is a collection of distinct ethnic and cultural areas that is ruled by one specific political/cultural entity among them, leaving the rest feeling distinct and disenfranchised. It can consist of contiguous or non-contiguous provinces — or it can consist of different planets, of course.

So that’s an empire. It doesn’t make much difference, of course, if all you want to do is boo the Evil Emperor — but hopefully it might help if you’re trying to make sense of the political state of the world you’re creating.

1 Wu Zetian, Empress of China from 660 to 705, is a notable exception.

2 Some used variations of imperator, some of the name Caesar that became a synonym of emperor. These included the German Kaiser (actually, closer than our pronunciation to the original) and the Russian Tsar or Czar.

3 Approximately. Other similar phrases have been suggested.

4 This was the normal form until several centuries later — King of the English, King of the Franks, King of the Germans etc. The Kings (and Queens) of Scots maintained this form until the union of the crowns in the 17th century, while the Belgian monarch is still styled King of the Belgians.

5 That’s the theory, at least.

Image: The Coronation of Charlemagne by Maximilianeum München, 1903 (public domain)

Hanging Out With the Kids — Recent YA Fantasy TV

In general, the best stories don’t have an upper age limit, and this fact has been traditionally recognised in fantasy more than most genres. The Hobbit, the Chronicles of Narnia, His Dark Materials — they were all published as children’s books, and the all-ages phenomenon of Harry Potter put kids’ books and films firmly on adult reading/watching lists.

Over the decades, I’ve watched plenty of children’s TV series, both as a kid and later, but that eventually tailed off — until The Sarah Jane Adventures came along. The for-younger-viewers companion of Doctor Who (my favourite TV show since I watched the first episode at nine), I found it excellent, rarely if ever dumbing down for the kids.

So I gradually started looking for other children’s and young adult* fantasy and SF shows to watch. I’ve seen a number in recent years (some OK, some good, some excellent), so this is a round-up of a representative selection. On the whole, I’ve concentrated on the zone at which children’s and YA interface, rather than shows for younger children or for older young adults.

Wolfblood

After The Sarah Jane Adventures, Wolfblood was the show that got me really enthusiastic about younger fantasy TV. This is a werewolf story, with the difference that no-one changes into wolf-like monsters. They change into actual wolves — loyal, fun-loving and far more afraid of us than we are of them.

The story follows a group of teenage wolfbloods and their friends, trying to cope with school, romance and other teenage affairs, while keeping their secret. Although occasionally falling into silliness, for the most part it does a great job of exploring the moral, social and emotional dilemmas this raises, as well as crucial issues about the relationship between civilisation and nature.

I did feel the standard dropped slightly after series 2, when the original main character left, and then against after series 3, when it largely had a change of cast, but the show remained well worth watching. The final resolution, at the end of series 5, was a little unrealistically fast, but still satisfying.

Theodosia

The teenage daughter of Edwardian Egyptologists accidentally acquires magical powers and has to use them, helped by her brother and friends, to save the world by fighting sinister cults and evil gods. That’s got to be great. Well, it is, but…

Theodosia is huge fun, but it’s also extremely frustrating. It’s made with no regard at all for the period it’s set in. Everyone speaks in modern slang, and Theodosia and her friends not only don’t behave like Edwardian kids, but aren’t treated like them either. And then there’s the “Egyptian princess” who claims to be descended from the pharaohs and knows all about worshipping the ancient gods — even though the ruling family at the time were Muslims of Albanian descent.

So does that matter? Well, it’s unlikely the target audience would notice any of this, but in a way that’s the problem — it’s misinforming them. Still, Theodosia is enjoyable to watch, if you can ignore these flaws.

The Bureau of Magical Things

This is an Australian show, following the now-standard trope of a magical world (here largely elves and fairies) hiding in plain sight among the ordinary world of humans. In the usual way, an outsider finds she has powers and gets a crash course in the magical world, helped by a group of kids her own age who welcome her with varied levels of enthusiasm.

There’s nothing particularly original here, but it’s engaging, the story builds well, and the acting is OK, without being award-winning. There were just two series, and the second had a pretty much definitive ending, with a resolution rather reminiscent of Wolfblood, but stretching the credulity rather more.

The Sparticle Mystery & The Cul de Sac

Every so often, two films or TV shows will turn up around the same time, taking the same basic idea and running with it in different directions. This happened with these two shows, which I watched close together in time.

The idea both used isn’t at all new — kids find that every adult has disappeared, and they have to learn to manage on their own. In The Sparticle Mystery, this turns out to be due to a scientific experiment gone wrong. The main kids are a mixed bag of all ages (for a wide age-range appeal?) who are trying to find out what’s happened and how to reverse it.

The show has its appeal, but it does have shortcomings, too. The acting is variable, and the situations grow more improbable over the three series. Most of all, it moves its goalposts onto a totally different pitch. We start out in solidly SF territory, but by the end the solution to the scientific dilemma proves to be ancient Celtic magic. Now, I love ancient Celtic magic as much as anyone, but not when it turns up unbidden in SF.

The Cul de Sac, on the other hand, is a New Zealand show with a much harder edge and no inconsistencies I noticed. Here, the kids not only have to struggle to survive against a far more serious threat than any in The Sparticle Mystery, but they’re also menaced by a daily “wave” that disintegrates anyone caught outside when it passes.

The explanation here is much more bizarre and intriguing than in The Sparticle Mystery, and I’d rate it as a much better show — though I suspect that may be partly because it’s aimed at a slightly older audience. It finishes with both a resolution and a tease for a possible sequel, though that hasn’t happened.

World’s End

This is a curious, atmospheric SF show, where a group of teenagers are gathered in a remote Scottish castle run by an unofficial collection of military and scientific personnel (many of them the young people’s parents) and discover they all have doubles. The kids eventually discover an ambitious plan to counter a threat to Earth.

The science in World’s End stretches the credulity a long way, the acting is patchy, and one or two characters threaten to tip over into caricature, but the story is still compelling. Unfortunately, although series 1 finishes with not one but two major cliffhangers, no series 2 has materialised, and many of the original cast would be far too old by now.

Paper Girls

Another show annoyingly cancelled after series 1, Paper Girls is the only US show in this collection — probably more to do with access than quality. It starts out as if it’s going to be a Stranger Things clone, with four twelve-year-old 1980s girls having their world turned upside-down by a bizarre event.

After that, however, it goes its own way into a time-travel story. The girls get caught up in a future civil war over the control of time-travel technology and whisked to various points between the 80s and now, in the course of which most of them meet their older selves.

I found it excellent, and the reviews I saw were mainly very positive, which makes it even more aggravating to be left permanently on a cliffhanger. The only negative comments I saw were the usual suspects whinging about “woke casting” — i.e. daring to include characters who weren’t white and straight.

Heirs of the Night

Based on a German novel, Heirs of the Night was made by a group of companies from various European countries, although the default language is English. Set in the late 19th century, this is a story about ancient vampire clans battling against both fanatical vampire-hunters and Dracula attempting to gain control over both the vampire and human worlds.

Unsurprisingly, the key to defeating both is a teenage vampire girl who is the Chosen One. The young vampires who are the main characters are well drawn, and the story’s exciting, even though the “good” vampires seem rather unrealistically harmless. Oh well, at least they don’t sparkle.

Silverpoint

I started watching Silverpoint without any high expectations. A group of kids exploring in the woods find a mysterious alien artefact… yawn. In fact, I got very quickly sucked in, and it’s probably my second favourite of the shows I’ve highlighted here, narrowly behind Wolfblood.

Both the four principals and the various supporting characters are well drawn and well acted, and the story quickly became compulsive. There are plenty of surprising twists and turns, including one mid-season flip in series 2 that I genuinely didn’t see coming.

Series 2 came out last year and ended with the promise of more to come. With IMDb scores of 8 or 9 for most episodes, I’m hoping that means we’ll be getting series 3 later this year.

There are other shows I could mention, but hopefully you may be encouraged to check out some of these. Certainly, if you have access to BBC iPlayer, I’d recommend anyone who loves SFF to check out Wolfblood and Silverpoint, at the very least.

Of course, I’m not suggesting all TV should be kids’ stuff, even great kids’ stuff. I enjoy grittier shows as much as anyone, and I’m eagerly looking forward to the new series of Stranger Things and The Witcher, among others. But, just as there shouldn’t be any problem about enjoying both the Harry Potter books and A Song of Ice and Fire, the best fantasy and SF TV for younger people can provide plenty of enjoyment for adults, too.

* I find the boundaries between both children and YA, and YA and adult, extremely vague. Perhaps that’s partly because there wasn’t such a thing as a YA category when I was a young adult.

What’s in a Surname?

It used to be simple enough. Fantasy names were Conan the Barbarian, Elric of Melniboné, Aragorn son of Arathorn. That even applied to sophisticated SF races: Vulcans and Klingons made do with a single name each, for instance. No self-respecting fantasy character would have such a thing as a surname — unless, of course, they happened to be a Hobbit.

Things have changed considerably now, but there still persists the idea that people in the old days didn’t have surnames. But “the old days” never really existed, and if they had, they’d have been a lot more complex than people tend to assume. And that includes surnames.

Why Do We Use Surnames?

Broadly speaking, there are three conditions required for the development of surnames — a relatively small supply of personal names, a society where each individual comes into contact with many people, and some degree of bureaucracy in social structures. While surnames may arise without all three, these are generally the driving forces.

Early in human history, your tribe might have consisted of no more than two or three dozen individuals, and the choice of names (whether given at birth or initiation) might well be varied and creative. You might encounter someone with the same name at a larger gathering, but that was easy. If your name were Running Deer, for instance, you’d be Running Deer of the Wolf Tribe, rather than Running Deer of the Bear Tribe.

In post-Conquest England, however, things got tricky. The extensive choice of Anglo-Saxon names were quickly replaced among the peasants by a small number of Norman-introduced names.1 So a quarter of the men in the village might be called John, for instance, and it became necessary to distinguish between them.

This led, very soon after the Conquest, to the use of informal surnames to distinguish people with the same name. John who lived by a hill, for example, might be called John Hill; but his son, also John, who went to live by a brook, would become John Brook.

Nevertheless, these informal names gradually became formalised and hereditary. And this process took place across Europe, although not always at the same speed. In fact, Iceland still doesn’t use surnames, just a personal name and a patronym.

Surnames in the Ancient World

These weren’t by any means the earliest surnames used, though. A number of ancient societies had formal and universally used surnames, the best known being the Romans and the Chinese.

The Romans (in contrast to the Greeks, who stuck to patronyms, such as Pericles son of Xanthippus) had developed a complex naming system long before the end of the Republic in the 1st century BC. The nobility had three names: a personal name, a family name and a clan name. Thus Gaius Julius Caesar was Gaius of the family Julius, of the clan Caesar. The common people, on the whole, just had a personal and a family name.

The Chinese certainly had surnames (which came before the personal name) by the 3rd century BC, and probably earlier. The founder of the Han Dynasty, at the end of that century, was a man called Liu Bang, Liu being his surname. Since he was born a peasant, this suggests surnames were universal. At this time, personal names were normally just one character, though later two-character names became normal.2

What Roman and Chinese societies had in common was the need to define and record individual people. The most obvious reason for this was for taxation, but there were other civic requirements (military service, for instance) that meant the bureaucrats needed to identify individuals precisely.

Surnames in Fantasy Worlds

So should fantasy characters have surnames? Well, that depends on what kind of society they belong to. If they’re from a primitive tribe, probably not, whereas if they live in a large and well-organised nation (especially in a city), they’re almost certain to need one.

That doesn’t mean, though, that they have to be a boring personal name/surname structure. Full names can encode various information, as well as coming in different orders. In Russia, for instance, they traditionally used both a patronym and a surname. Lenin’s original name, Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, indicated he was the son of Ilya Nikolayevich Ulyanov, and his social acquaintances (as opposed to close friends) would have addressed him as Vladimir Ilyich.

I’ve used a similar idea for one particular society, where people have three names, with combinations used in different social contexts. For example, there’s a character called Fel Arith Fugon. Arith is his surname, and he might be addressed formally as Master Arith, while his close friends and family would call him Fugon. More casual acquaintances, though, would call him Fel Fugon, with the first name (always one syllable) only ever used in this combination.

I also have societies where the surname is preceded by a short word, roughly equivalent to de in France or von in Germany. For instance, the protagonist of my story The Guild’s Share, published late last year, is Loshi vi Assarid.